(Monterey Bay, and its Cannery Row)

As a schoolgirl, one boy always followed me around. Before leaving for school, my mother always used a curler (how many of you remember them?) on my hair, and he liked watching my curls bounce up and down as I walked. Another boy, when I wore Pigtails, would tip their ends in his inkwell. I never could get interested in history, not understanding why I had to memorize the spelling of so many names and when people were born and died.

When I matured and started traveling around the world, I became very interested in the culture and history of wherever I went, and studied up on everywhere before going there, sometimes knowing more than my travel agent or my guide. The more I saw and learned, the more I wanted to see and learn. Therefore, my articles have lots of history. I want to bring back memories to those that have been there, and make those that might never get to these places, feel like they have been there.

One of the most historic places my husband Lloyd and I visited was Monterey Bay and Cannery Row. The first European to Monterey Bay was Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in 1542, and high seas prevented his landing. In 1602, Spanish explorers charted the Monterey Peninsula, settled in 1770, when Franciscan Priest Junipero Serra, and Spanish Governor Gaspar de Portola, appeared, constructing a mission.

The ships, “La Argentina” and “Santa Rosa,” claimed Monterey (down to Dana Point) for Argentina in November 1818. Refilling their larders, they sailed south, plundering and burning. Because Argentina did not pursue its claims, this was California’s only active interaction with outside revolutionists throughout the Spanish-American Wars of Independence.

Just about anything significant in California from 1770 to 1848 was in Alta California’s capital, Monterey, and under the Spanish, Mexican, and American flags. Seven-acre Monterey State Historic Park has about nine adobes, and other buildings, conserving Monterey’s historical and architectural heritage. The Royal Presidio Chapel, erected by the Spanish in 1794, is the oldest structure.

Lloyd and I strolled around the historic old Fisherman’s Wharf, once the heart of Monterey’s fishing trade. Constructed in 1845 for trading vessels transporting provisions around Cape Horn, Monterey was the key port on the Pacific Coast. The thriving whale industry took over the Wharf, but the diminutive sardine made Monterey an industry front-runner. Besides sardines, were albacore, mackerel, rock cod, salmon, squid, and tuna, and we delighted in the best of fresh seafood.

Fisherman’s Wharf had many transformations, and we visualized trading ships, fishing boats, and whalers. The Whaling Station once was a boarding-house for Portuguese whalers and has a diamond-patterned sidewalk crafted from whalebone. We saw the original 1602 landing place of Sebastian Vizcaino, and Father Junipero Serra (over 150 years later).

Throughout the 1850s, Chinese fishermen gathered and dried out salmon and squid. In 1906, their China Point community burned under strange conditions, and they moved to McAbee Beach, where there are exhibitions about Portuguese whalers laboring here in the 1860s.

The rapid expansion of the Monterey fishing trade began the fish canning industry and Cannery Row. In February 1908, the first major cannery on Ocean View Avenue was the Pacific Fish Company. The huge Hovden Food Products Corporation was established in July 1916 by Knut Hovden, a Norwegian immigrant, and Hovden was the king of Cannery Row’s sardine-canning establishments.

Fishing and canning know-how prepared Monterey for canned sardines, around the time of World War I. The canneries increased, and Cannery Row canneries lined the seashore. (Cannery Row’s wartime production went from 75,000 cases in 1915, to 1,400,000 in 1918). Slowing throughout the Great Depression, World War II saw another increase in the canning industry.

Cannery workers, primarily immigrants, were called to work by cannery whistles, each having a distinctive sound. The workday began with the night catch, continuing until the day’s catch was canned. There were no rules for hours and shifts, and cannery employment was long, chilly, malodorous, and hazardous.

The original canneries obtained fish from a pier. Laborers cut fish separately by hand, detaching heads and tails, then scattering them to dry on wooden slats. Big metal baskets of fish then went through boiling peanut oil, drained, put into cans, and were soldered by hand. Labeling and boxing was the final step. Crossovers, linking the bay-side of the street, we saw remnants of the conveyor belts that conveyed cans.

From the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s, up-to-date fishing practices and canning and processing plants, took their toll, and the sardine abundance collapsed in the late-1940. When former Hovden Food Products Cannery packed the Portola brand of sardines, Cannery Row had 17 to 19 working fish canneries. By canning squid, Hovden Cannery outlasted its neighbors, closing its doors in 1973, being the last cannery to shut down. Along the waterfront, Cannery Row now has outdated sardine canning factories.

Hovden Way Promenade allowed us access to the bay, where we watched seals barking and lazing on the rocks, seagulls wheeling and feeding (consuming up to 20 percent of their weight daily, seeking food in kelp beds), and playful otters. Until 1911, otters were pursued for their pelts. Thought to be approaching extinction, a raft of otters was spotted around Big Sur in the 1930s.

In April and May, sea lions swim to Southern California, to breed in the Channel Islands. Male elephant seals fight and breed for months, then get fatigued (I should think so), a foremost male feasibly having 100 females in his harem. Female elephant seals dive deeper (1,250 meters) than other recorded creatures. Mature bulls weigh between 3,000 to 5,000 pounds each, and the newborns weigh 70 pounds.

We strolled around John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row, where sardine harvesting generated Monterey’s Cannery Row through the 1920s. In 1935, Cannery Row was Steinbeck’s stimulation for his earliest popular novel, “Tortilla Flats,” featuring Cannery Row individuals. The street name, formerly a nickname for “Ocean View Avenue,” became approved in January 1958 to honor John Steinbeck and his renowned novel “Cannery Row.”

The sardine canneries were replaced by galleries, shops and restaurants, and we went to the Cannery Row Edgewater Family Fun Center, to see the colorful carousel, with lovely paintings on its top.

Monterey Bay is a microcosm of the open ocean, and several foremost marine research facilities surround the bay. The book, “Between Pacific Tides,” written by Edward F. Ricketts, helped present the understanding of ecology to marine biology. Ricketts was the stimulus for several characters in Steinbeck novels, memorialized as the specimen-collecting Doctor in John Steinbeck’s 1945 novel, “Cannery Row.”

Rickett’s biological supply house, a ramshackle laboratory, was at 800 Ocean View Avenue (now Cannery Row), from 1928 to 1948. In a weather-beaten clapboard bay-view building, his Pacific Biological Laboratories is now the Monterey Men’s Club.

After World War II, the over-fished sardines collapsed, from adverse oceanic circumstances, over-fishing, and rivalry from other species, bringing misfortune to Cannery Row. The locale nearly went into devastation, but Steinbeck’s “Cannery Row” transported readers to experience the atmosphere of the renowned street, where we saw beautiful fence murals, which not one person even glanced at, as they walked by.

Before the downfall, Monterey’s fishing business was one of the most prolific in the world, with the upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, channeled to the surface by the massive underwater Monterey Canyon. On the scale of the Grand Canyon, Monterey Canyon is the largest submarine chasm along the continental U.S. The 70-mile-long trench, including Carmel Canyon, drops to over 10,000 feet. Sculpted from granite, shale, and sandstone, Monterey Canyon was born 25 to 30 million years ago. Pressed along the San Andreas Fault, as part of the Pacific Plate, much of its magnitude is because of constant seismic movement.

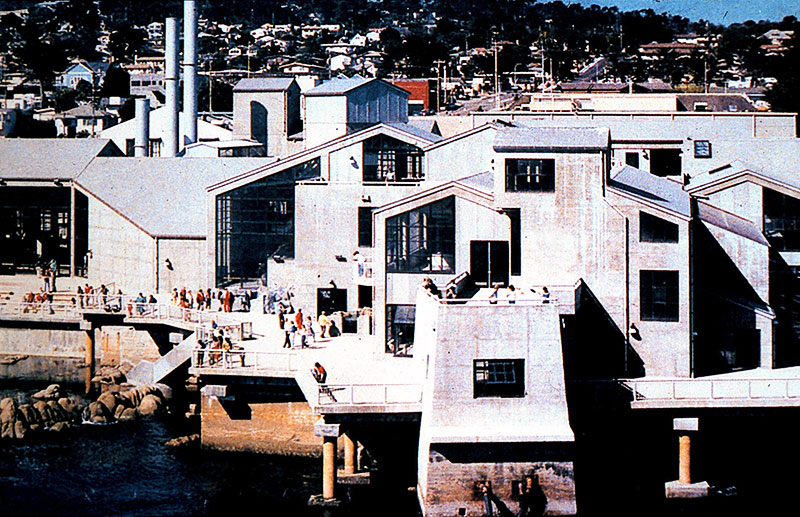

The bay’s ecological importance encouraged David Packard, co-founder of electronics goliath Hewlett Packard and his wife, to begin construction of the aquarium devoted to a single ecosystem. They invested $55-million, and in 1987, they gave another $20-million to launch a related research institute.

In 1984, the cannery reopened as the magnificent Monterey Bay Aquarium, with the inhabitants and varied environments of Monterey Bay. We noticed a Portola sardine trademark painted onto the outside of the aquarium.

One of the world’s loftiest aquarium exhibits, the 28-foot-high Kelp Forest, is open to the sky. Fed by pumped-in bay water, having fresh nutrients, sushi lovers welcome the rubbery kelp fronds. We watched kelp climbing over twenty feet from the bottom, swaying with the rhythm of the ocean.

For dinner, Lloyd and I went to the ocean-side Bubba Gump Shrimp Company Restaurant and Market. We enjoyed a huge char-broiled salmon, brushed with herbs, served with sour cream mashed potatoes, followed by an old-fashioned ice cream sundae.

After an enjoyable evening at Bubba Gump’s, with their great seafood and memorabilia from the movie, “Forrest Gump,” Lloyd and I retired for the night at the Monterey Plaza, a world-class bay resort, with two award-winning restaurants, centrally located on Cannery Row.

Old Hovden Cannery steam boiler.

Monterey Bay Aquarium, with Portola Sardines sign.

Find your latest news here at the Hemet & San Jacinto Chronicle

Search: Monterey Bay, and its Cannery Row