Late last month, the San Francisco-based startup HeHealth announced the launch of Calmara.ai, a cheerful, emoji-laden website the company describes as “your tech savvy BFF for STI checks.”

The concept is simple. A user concerned about their partner’s sexual health status just snaps a photo (with consent, the service notes) of the partner’s penis (the only part of the human body the software is trained to recognize) and uploads it to Calmara.

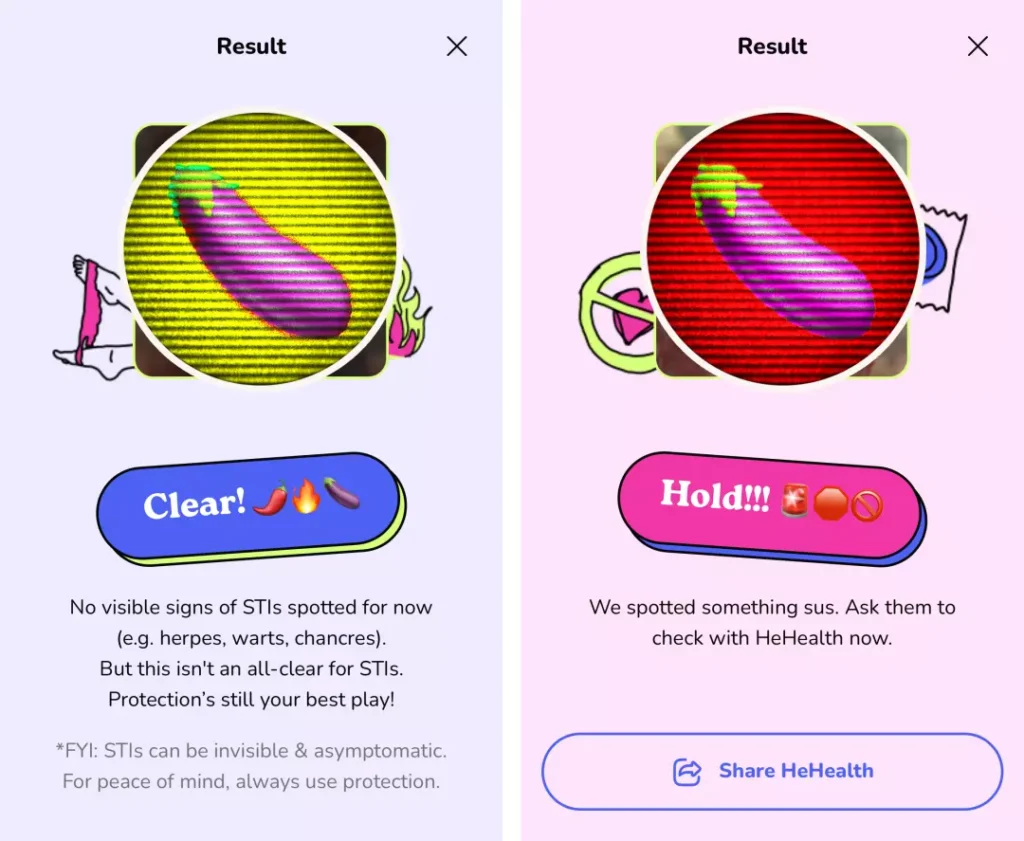

In seconds, the site scans the image and returns one of two messages: “Clear! No visible signs of STIs spotted for now” or “Hold!!! We spotted something sus.”

Calmara describes the free service as “the next best thing to a lab test for a quick check,” powered by artificial intelligence with “up to 94.4% accuracy rate” (though finer print on the site clarifies its actual performance is “65% to 96% across various conditions.”)

Since its debut, privacy and public health experts have pointed with alarm to a number of significant oversights in Calmara’s design, such as its flimsy consent verification, its potential to receive child pornography and an over-reliance on images to screen for conditions that are often invisible.

But even as a rudimentary screening tool for visual signs of sexually transmitted infections in one specific human organ, tests of Calmara showed the service to be inaccurate, unreliable and prone to the same kind of stigmatizing information its parent company says it wants to combat.

A Los Angeles Times reporter uploaded to Calmara a broad range of penis images taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Image Library, the STD Center NY and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

(Screenshots via Calmara.ai)

Calmara issued a “Hold!!!” to multiple images of penile lesions and bumps caused by sexually transmitted conditions, including syphilis, chlamydia, herpes and human papillomavirus, the virus that causes genital warts.

But the site failed to recognize some textbook images of sexually transmitted infections, including a chancroid ulcer and a case of syphilis so pronounced the foreskin was no longer able to retract.

Calmara’s AI frequently inaccurately identified naturally occurring, non-pathological penile bumps as signs of infection, flagging multiple images of disease-free organs as “something sus.”

It also struggled to distinguish between inanimate objects and human genitals, issuing a cheery “Clear!” to images of both a novelty penis-shaped vase and a penis-shaped cake.

“There are so many things wrong with this app that I don’t even know where to begin,” said Dr. Ina Park, a UC San Francisco professor who serves as a medical consultant for the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention. “With any tests you’re doing for STIs, there is always the possibility of false negatives and false positives. The issue with this app is that it appears to be rife with both.”

Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, an infectious-disease specialist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine and a scientific adviser to HeHealth, acknowledged that Calmara “can’t be promoted as a screening test.”

“To get screened for STIs, you’ve got to get a blood test. You have to get a urine test,” he said. “Having someone look at a penis, or having a digital assistant look at a penis, is not going to be able to detect HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea. Even most cases of herpes are asymptomatic.”

Calmara, he said, is “a very different thing” from HeHealth’s signature product, a paid service that scans images a user submits of his own penis and flags anything that merits follow-up with a healthcare provider.

Klausner did not respond to requests for additional comment about the app’s accuracy.

Both HeHealth and Calmara use the same underlying AI, though the two sites “may have differences at identifying issues of concern,” co-founder and CEO Dr. Yudara Kularathne said.

“Powered by patented HeHealth wizardry (think an AI so sharp you’d think it aced its SATs), our AI’s been battle-tested by over 40,000 users,” Calmara’s website reads, before noting that its accuracy ranges from 65% to 96%.

“It’s great that they disclose that, but 65% is terrible,” said Dr. Sean Young, a UCI professor of emergency medicine and executive director of the University of California Institute for Prediction Technology. “From a public health perspective, if you’re giving people 65% accuracy, why even tell anyone anything? That’s potentially more harmful than beneficial.”

Kularathne said the accuracy range “highlights the complexity of detecting STIs and other visible conditions on the penis, each with its unique characteristics and challenges.” He added: “It’s important to understand that this is just the starting point for Calmara. As we refine our AI with more insights, we expect these figures to improve.”

On HeHealth’s website, Kularathne says he was inspired to start the company after a friend became suicidal after “an STI scare magnified by online misinformation.”

“Numerous physiological conditions are often mistaken for STIs, and our technology can provide peace of mind in these situations,” Kularathne posted Tuesday on LinkedIn. “Our technology aims to bring clarity to young people, especially Gen Z.”

Calmara’s AI also mistook some physiological conditions for STIs.

The Times uploaded a number of images onto the site that were posted on a medical website as examples of non-communicable, non-pathological anatomical variations in the human penis that are sometimes confused with STIs, including skin tags, visible sebaceous glands and enlarged capillaries.

Calmara identified each one as “something sus.”

Such inaccurate information could have exactly the opposite effect on young users than the “clarity” its founders intend, said Dr. Joni Roberts, an assistant professor at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo who runs the campus’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Lab.

“If I am 18 years old, I take a picture of something that is a normal occurrence as part of the human body, [and] I get this that says that it’s ‘sus’? Now I’m stressing out,” Roberts said.

“We already know that mental health [issues are] extremely high in this population. Social media has run havoc on people’s self image, worth, depression, et cetera,” she said. “Saying something is ‘sus’ without providing any information is problematic.”

Kularathne defended the site’s choice of language. “The phrase ‘something sus’ is deliberately chosen to indicate ambiguity and suggest the need for further investigation,” he wrote in an email. “It’s a prompt for users to seek professional advice, fostering a culture of caution and responsibility.”

Still, “the misidentification of healthy anatomy as ‘something sus’ if that happens, is indeed not the outcome we aim for,” he wrote.

Users whose photos are issued a “Hold” notice are directed to HeHealth where, for a fee, they can submit additional photos of their penis for further scanning.

Those who get a “Clear” are told “No visible signs of STIs spotted for now . . . But this isn’t an all-clear for STIs,” noting, correctly, that many sexually transmitted conditions are asymptomatic and invisible. Users who click through Calmara’s FAQs will also find a disclaimer that a “Clear!” notification “doesn’t mean you can skimp on further checks.”